What do Kirk Cousins's year-by-year stats tell us about 2021?

The Vikings' QB said he's watching all of his career film to learn more about his game... what about his yearly numbers?

By Matthew Coller

If Packers president Mark Murphy can describe Aaron Rodgers is a “complicated fella,” we could call Kirk Cousins a diligent fella.

Cousins has been known to seek out every possible edge, from working with the Vikings’ analytics folks to hiring a mental coach to keeping his notes from every game and on and on.

Cousins revealed this week that this year’s offseason project was to watch back his entire career on film.

“That time looking at tape through the winter and spring, and even now as I go home through the summer after next week, I do think that it’s helpful now to see what has worked in the past, what I want to make as a staple for myself as I move forward…also where I have improved and where I need to improve,” Cousins said.

The Vikings’ QB explained that he wanted to “study, create cutups and really build some volume” that he could reference going forward. He set himself up with the film at his house so he could study it without going to the facility.

“Evaluation certainly comes from your coaches, day-in and day-out, but there’s also got to be an ability to self-evaluate and say, ‘I like what I’m doing there; keep doing that,’ or, ‘That’s not good enough — I want to improve that,’” Cousins said. “I think being self-led and being tough on yourself, too, can really help you as you watch tape that you put out there.”

Cousins also explained that watching the tape as a whole made him think more about getting the most out of his teammates and adapting how he plays to what they do best.

“You realize that the way Pierre Garcon ran a route or Desean Jackson ran a route, that affects you in the way you play and the way you think, and then you come to a new team and you’re trying to tell Adam Thielen to run a route that way, and he’s saying, ‘No, I don’t do it that way,’” Cousins said. “So just the process of then learning those players and saying, ‘OK’ and understanding that you always have to be aware of what your teammates do well and try to put them in those positions to be successful.”

Interesting stuff, right?

My first inclination when I heard Cousins’s comments was to consider repeating an abridged version of the exercise — to watch games from each season and write about them. But last year, I did a similar piece and talked with Cousins about his first career start and how far he’s come. You can read that here if you missed it.

So what other way could we investigate the course of Cousins’s history to learn about his future? Well, through the numbers.

Let’s have a look year by year at some of the in-depth stats that can point us toward where he’s changed and what trends might point us toward what’s to come…

Pre-2015

One comment Cousins made about his film analysis pertaining to his early years as an NFL quarterback is absolutely backed up by the stats: Washington had to be patient with him because there was more bad than good.

“I’ve watched myself in ’12 and ’13-14 and think, ‘Man, I’m such a better quarterback now,’” he said. “I can’t believe that the coaches didn’t just cut me when I did that and made that mistake. I can’t believe they were patient with me. Because nowadays looking back, it would just be unacceptable to myself, allowing myself to play that way or make that read or make that throw or that decision.”

Over his first three seasons, Cousins won just two of nine starts, threw 18 touchdowns and 19 interceptions and produced a 77.5 rating. He graded well by PFF standards in 58 attempts as a rookie and then looked very much like a replacement-level QB in 2013 and 2014, scoring a 51.4 (out of 100) and 58.1 in those years, respectively. For comparison’s sake, those grades would be lower than Drew Lock’s last year and about on par with Nick Mullens.

Even if it was a small sample size early on, few QBs who play that way ever find themselves in a position to become a full-time starter, much less have an eventual jump to being in the top half of the league consistently.

You would need a microscope to find the flickers in his 2014 season. Cousins did average 8.4 yards per attempt and suffered from an unfortunate string of drops (receivers dropped 12% of his passes) but his turnover-worthy play rate was seventh highest in the NFL among QBs with at least 100 drop backs.

That’s generally a tough thing to fix, yet in 2015, reducing turnover-worthy plays made all the difference in Cousins emerging as an NFL starter. He dropped from 4.8% of his throws being “turnover-worthy” by PFF standards to 3.2% in 2015. That rate has surprisingly remained constant through the rest of his starting career.

More than anything, his early struggles and eventual growth suggest that being a diligent fella pays off.

2015

When we talk about Cousins’s career, we generally begin with “since 2015.” That’s when he won the starting job in Washington out of training camp and started his first full season. The first three years were mostly periodic starts mixed in between Robert Griffin III and Colt McCoy. The 2015 season is the point in which we can begin comparing apples to apples with his subsequent full seasons.

One of the most interesting things about Cousins’s career has always been the ups and downs that he goes through each year. We often just look at the final results and determine what type of season a QB put together but in the case of 2015, he started remarkably slow and then got blazing hot in the second half. That happened in 2020 as well. Here’s his cumulative QB rating after each week in 2015 and after each week in 2020:

This exact pattern is not followed through every season of Cousins’s career but there’s always been some version of it. Through eight games in 2017, his rating was 102.0 and then he managed just an 85.8 rating the rest of the way. In 2018 he started hot and ended cold as well. In 2019, it was a slow start and hot middle of the season.

Is this the case with every quarterback that generally grades in the upper-middle part of the league? It would appear so. Derek Carr’s 2020 season, for example, started out with a 110.0 rating over the first half of the year and 92.8 in the second half. Matthew Stafford had a 92.4 rating through eight games last year and 100.7 the rest of the way.

The elite QBs have less of this issue. Tom Brady, for example, was at 103.1 through eight games and 101.2 in games 9-16.

The natural follow-up question here is whether there’s a way to mitigate the cold streaks.

What’s interesting here is that it should already be happening by virtue of Cousins playing better football than he did in 2015.

In his first full year as a starter, he posted a 73.9 PFF grade. In 2020, his grade was a much better 83.5.

Some of the under-the-surface numbers show us that Cousins was protected by his scheme. He ranked No. 1 in passer rating with play-action and ranked No. 1 in yards per pass attempt on screens. His PFF grade without play-action has jumped from 68.0 in 2015 to 80.0 last year.

However it’s worth wondering how much the passing environment plays into some of these numbers. In 2015, the league-wide passer rating was 90.2 and last year it was 93.6 — a pretty big jump over just a few seasons. The nearly 10-point difference in PFF grade only resulted in Cousins being 14th in 2015 and ninth in 2020. His 83.5 would have been good for a top five grade in 2015.

Last year’s road games were also easier on quarterbacks, which may spin the numbers a little. In 2018 and 2019, Cousins’s non-play-action PFF grades were still better than 2015 but only by a few points at 73.6 and 74.2, ranking him 16th and 11th.

The league is also succeeding more with play-action than ever. Six years ago, Cousins was one of only five QBs over a 110 QB rating on play-action throws. Last year there were 13 over 110 and 16 over 109.

Looking through the lens of 2015 shows us that, while many of the same things that are true of Cousins now were also true about him as a first-time starter, Cousins has improved at a similar rate as the league has improved. That could explain why the hot/cold streaks aren’t much different.

Another thing that’s noticeable in terms of the hot streaks is Cousins’s ability to absolutely demolish bad defenses. In 2015, he played the 31st and 32nd ranked defenses in QB rating against and posted 124.7 and 158.3 ratings against them. Of the five games he took on top-15 defenses in QB rating allowed, he registered ratings under 90 four times.

Last year the Vikings played five games against top-15 pass defenses and the only win came versus Green Bay when Cousins threw 14 passes (though he did play well in the Vikings’ 52-33 loss to New Orleans). So the schedule seems to play a role in his streakiness.

What does all of this mean for 2021?

Cousins will have to continue to improve in order to get the same amount of production because the league isn’t likely to get worse at quarterbacking. But the Vikings play against the No. 1, 2, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14 and 15th ranked defenses in QB rating allowed from 2020 and even if some of those defenses can’t repeat their performances, offensive coordinator Klint Kubiak will still be tasked with finding ways to reduce the impact of good coverage on Cousins.

How can that get done? Maybe 2016 has some answers…

2016

For a quarterback who has been remarkably consistent in his numbers from year to year as a starter, the 2016 season stands out because Cousins threw for 4,917 yards, which is more than 600 above his next best season. Washington ranked 21st in rushing and finished 28th in yards allowed on defense, putting Cousins in position to be the driving force of the offense.

Cousins’s second full season as a starting QB was the only time in which his team has ranked in the top five in Expected Points Added through the air. Since 2016, every team that has reached the Super Bowl has had a top five passing EPA. So while other seasons have graded higher by PFF, none have been as productive as 2016.

One part of his impressive numbers from 2016 is similar to 2020: With a bad defense, Cousins often played from behind. More than 3,000 of his yards in 2016 came while trailing. Likewise, 2,701 of his 4,265 were racked up when trying to come back.

That doesn’t exactly mean he was the “garbage time” king in 2016 or 2020 though. It might point us toward a different conclusion: When offenses are forced into a position to have Cousins throw often, it can yield net positive results, even if there is a down side (as we talked about in 2015 with cold streaks).

When the score was only separated by one score (which made up 447 of Cousins’s attempts in 2016), Cousins still averaged 7.9 yards per attempt, which was only topped by Matt Ryan, Tom Brady, Drew Brees and Alex Smith and tied with Russell Wilson. Washington as a team produced the third best yards per play in one-score situations.

They were seventh in team yards per play in the first halves of 2016 games while calling 304 passing plays to just 179 runs, per Football Reference.

Unlike 2015, the 2016 version of Cousins pushed the ball down the field. His average depth of target was a career high 9.4 yards per throw and he produced his biggest big-time throw percentage (5.1%). Last year those numbers were 8.7 ADOT and 4.3% BTT.

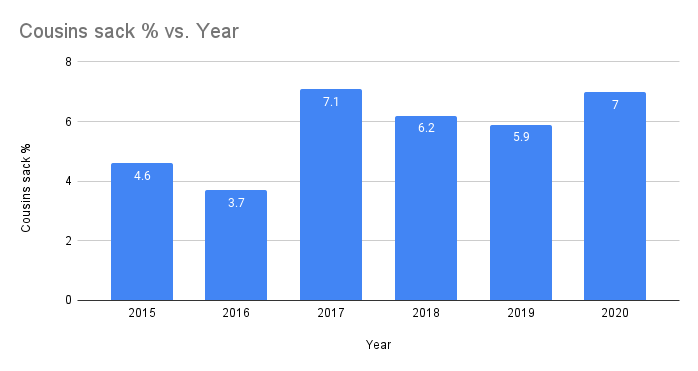

There’s one very interesting wrinkle to Cousins’s 2016 production that differs greatly from his time in Minnesota: Sacks.

While his time-to-throw was nearly identical, PFF graded Washington as the seventh best pass blocking unit in 2016 whereas the 2020 Vikings scored 29th.

A quick aside that’s noticeable: Pass blocking has gotten harder since 2016. Only three teams last season graded above 75. In 2016, 20 teams were above 75. Repeating Washington’s 2016 performance in front of Kirk might not be possible even if the Vikings improve the O-line greatly this year.

But it wasn’t just pass protection that helped Cousins. New PFF data shows that Cousins was responsible for just 4.8% of his own pressure in 2016, which was the fourth best in the league. Last year, he was responsible for 15.3% of his own pressure.

Subsequently his sack rate was 3.7% in 2016 and 7.0% last season.

It’s hard to put a finger on why he was responsible for so much more pressure last year than in 2016. We can only speculate that maybe he had fewer answers within the scheme or was concerned about the offensive line breaking down but it’s clear that is a necessary fix for 2021.

All said and done, 2016 had some of the same ups and downs as all of the other seasons. Washington lost four of its last six games to fall short of the playoffs and a top-rated pass defense slowed Cousins in Week 17 to eliminate them from the postseason. But 2016 provided a sample size of impressive output from a roster that was stacked around Cousins and leaned into passing the ball as the driver of the offense.

We shouldn’t expect to see anything similar to that in 2021 but there is a case based on his 2016 results to pass more often early in games.

2017

Cousins’s 2017 season is the answer to what happens if the Vikings have a bunch of injuries to their weapons. From 2016 to 2017, Cousins lost Pierre Garcon and DeSean Jackson and Jordan Reed played only six games. That pushed Jamison Crowder into the WR1 role with Ryan Grant, Josh Doctson and Terrelle Pryor making up the rest of the group.

Combined with the loss of weapons was injuries on the offensive line that sunk Washington to 26th in pass blocking by PFF.

That’s not to mention that Sean McVay left for Los Angeles.

Cousins dipped to 18th by PFF grade and to a 93.9 QB rating, his lowest as a starter.

There isn’t a ton to take away from 2017 other than: 1) We learned the floor for Cousins. When it all goes wrong, the team can still rank 16th in scoring but there’s a threshold that’s too much to overcome to make the postseason. 2) He still ranked second in play-action, giving credence to the idea that even under bad circumstances, Cousins can still thrive with play-action.

2018

Speaking of which, the 2018 season was a test case for what happens when the offensive coordinator asks Cousins to play in a dropback offense rather than a play-action scheme. John DeFilippo only dialed up play-action throws on 20.8% of passes in 2018, in comparison to 31.1% in 2019 and 28.7% last year. Cousins was still very successful in play-action but without it he only averaged 6.7 yards per attempt.

The consistent theme throughout this look at his career numbers is that under advantageous situations, Cousins can blow the roof off. In 2017 and 2018, with some things that weren’t in his favor, we see a decided dip from 2015/2016 and 2019/2020.

Again, this is true for many quarterbacks. See: Goff, Jared.

But it feels more pronounced with the peaks and valleys. When things went sideways in 2017, Washington fell out of the playoff race. Same for 2018 when Cousins had a stretch of three losses in four games and he didn’t produce a PFF grade higher than 61 in the three losses. That leaves little room for error during the good stretches. A kicker can’t miss three field goals or a defense can’t give up 400-plus yards passing to the Rams, for example.

We also saw in 2018 that speeding up Cousins’s delivery with more quick throws didn’t exactly correlate to fewer sacks or less pressure. He was still sacked 40 times and had the second most total pressured dropbacks. Interestingly, however, the offensive line was responsible for 89.8% of the pressure. That appears tell us that the 2018 line was not designed to handle a huge amount of dropback passes and speaks more to the offense being a misfit for Cousins.

That said, not all of the 2018 ideas were bad. More than 50% of Cousins’s passes were between 0-9 yards in 2018 (fourth most). That dropped to 46% last year despite Cousins grading as the fifth best short passer in the NFL by PFF grade. He also produced just four turnover-worthy plays when throwing short and had a 111.1 QB rating (third best).

As much as the Vikings want to hit on throws downfield, their short game was effective when used last year. And it’s one of the areas where Cousins has improved since his early starting days. He graded 19th on quick passes in 2016.

2019/2020

Over the last two seasons the Vikings have settled into a system that works for Cousins but doesn’t lean heavily on him. Between 2019 and 2020, Tom Brady threw 690 passes in the first halves of games while Kirk Cousins threw 471 times in the first half. He ranked 17th in first/second quarter passes in 2020.

Cousins is part of a trend in the NFL of teams that are run-focused but aim for high efficiency in the passing game. Ryan Tannehill’s resurgence has been based around this idea. Jimmy Garoppolo, Jared Goff and Baker Mayfield also fall into this category.

But there’s a question of whether a more conservative gameplan with an eye on explosive plays can take the Vikings to the next level. Despite pushing the ball downfield, Cousins was only 18th in big-time throw percentage last year. His average depth of target was 14th. That means he isn’t being particularly aggressive in an offense that already isn’t aggressive by nature.

The only season in which Cousins ranked in the top 10 in big-time throws was 2016, by the way. With Justin Jefferson and Adam Thielen being either on par or better than Garcon and Jackson, there’s a strong case for ramping up that aggressiveness again.

Recap

So here’s what we learned:

— Cousins’s ups and downs are standard for QBs of his ilk but mitigating the downs, especially against good competition, could widen the margin for error in games where he plays well. How they go about that will be a conundrum for Cousins and Kubiak to solve.

— Cousins has improved over the years but the league is not static, so he’ll need to continue to raise the level of his game to stay on par with an ever-improving passing league.

— Cousins brought more pressure on himself in 2020 than other years. That has to be resolved or the impact of an improved offensive line will be limited.

— The Vikings’ QB has been the benefactor of remarkable receiving talent in every season since 2017 and when it wasn’t present, his performance slipped. The Vikings having no backup plan at receiver for Jefferson and Thielen is questionable.

— Cousins was effective in the short passing game, which was reduced over the last two years.

— Because Cousins isn’t an aggressive QB by nature, manufacturing aggressiveness may be the only way to reach the “next level.”

Support the businesses that support Purple Insider by clicking below to check out Sotastick’s Minnesota sports inspired merchandise:

Good stuff, Matthew. If nothing else, Cousins should be credited with maximizing his earning potential as a somewhat-better-than-average quarterback. I've recently re-watched a few of his good performances from the 2018 season (such as Philadelphia), and wonder what a full season of "let's let Kirk drop back and put it on his shoulders" would look like. Then I watch the Buffalo game. In all things, the better you get at it, the harder it becomes to improve. I'm hopeful that the planets will align this year, and Kirk (and the offense) can squeeze every ounce of potential from his arm.

Great article Mathew